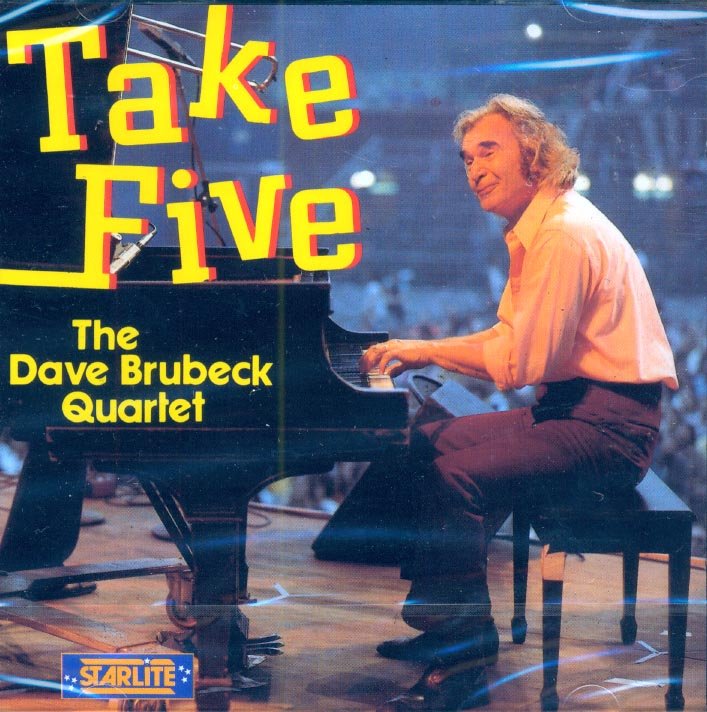

“Blue Rondo à la Turk” in a crazily sliced 9/8 was born there, and so was Brubeck’s lasting popularity. On tour, he heard local musicians playing odd rhythms and decided right there that he’d make a jazz album employing unusual time signatures. It’s found in avant-garde music or in folk traditions tucked away in Hungary, India. “Take Five” added one little beat to the normal 4/4 pulse and made it 5/4, an unheard-of time signature for jazz. People like to look at faces, especially of celebrities, but there were no photos of the popular musicians greeting the public, just egg shapes and abutting slaps of color.īut the biggest risk, of course, was the music. No comforting “standards” were on it to reassure buyers wary of new music.įor another, the cover art was a contemporary, abstract painting. For one thing, it was a jazz album with nothing but original pieces. It broke many conventions in achieving that. Led by the hit single “Take Five,” written by alto saxophonist Paul Desmond, Time Out was the first jazz album to sell a million copies. Brubeck’s face had been on the cover of Time magazine in 1954, Jailhouse Rock came out in 1957, and it would still be two years before the Quartet had its incandescent burst into the stratosphere-and into jazz history-with the release of Time Out. The Dave Brubeck Quartet was already one of the hottest ensembles in jazz in the ’50s, playing hundreds of concerts, and releasing multiple LPs, every year. Hollywood knows a good stereotype when it sees one, hick or slick, and “Brubeck” meant cerebral, cool, West Coast. Rather than revealing his ignorance, he barks crudely at her and stalks out. Elvis’s increasing discomfort wells up when the hostess asks his opinion.

They toss around lingo like “dissonance” and “atonality,” and the names of some musicians, including that of Dave Brubeck. He’s dragged to a swanky party, where he’s wedged between society snobs who try to look intellectual and hip by discussing modern music. In Jailhouse Rock, Elvis plays an ex-con rube hoping to make it in the music business.

All else is secondary.īrubeck died on December 5, 2012, in Norwalk, Connecticut, on the eve of his 91st birthday.(Originally published in 2015).

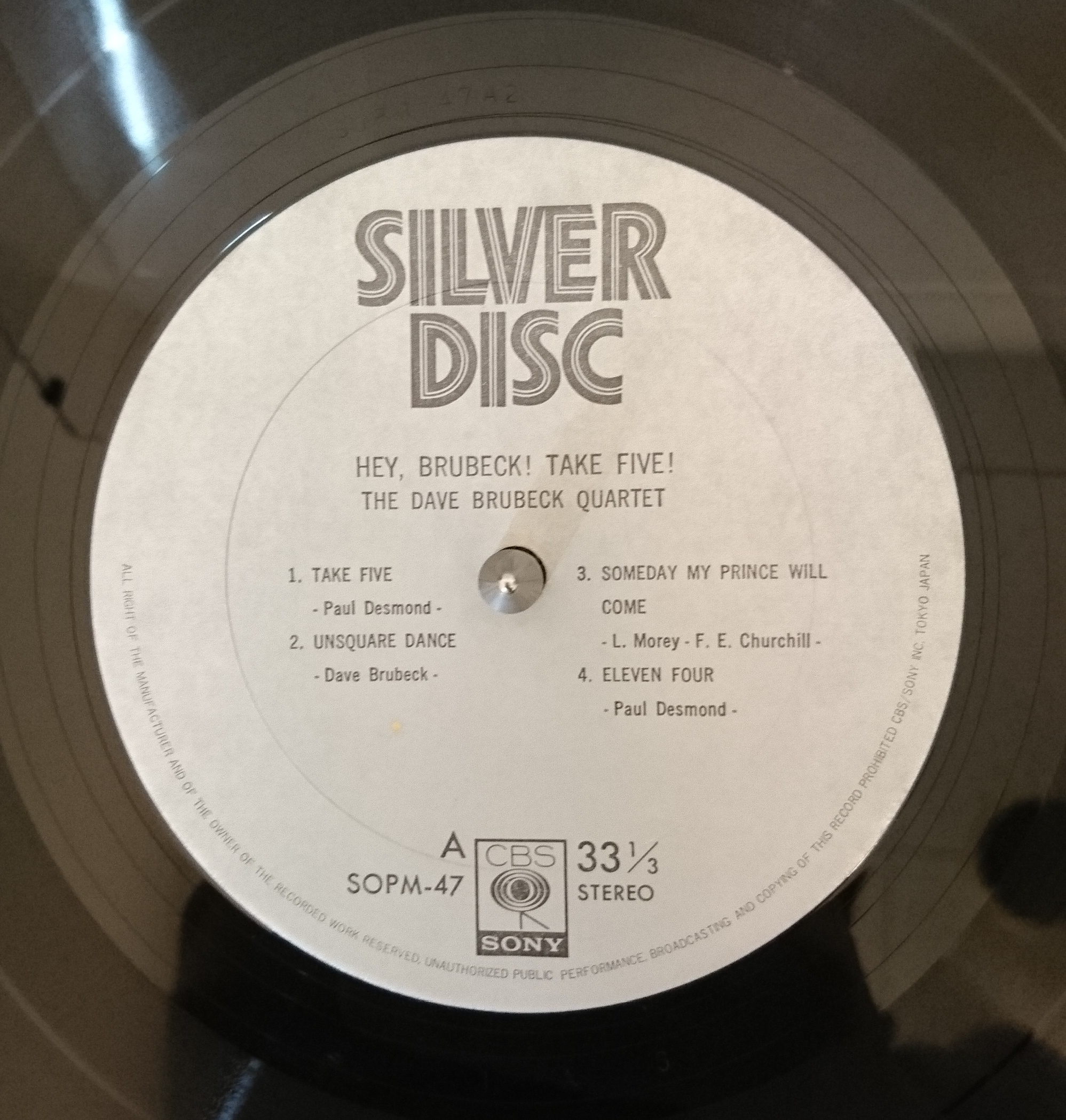

It affirmed his faith in his musical instincts and taught him the most important lesson of all: follow the music first wherever it leads. It was a huge success - “Take Five” became the greatest selling jazz record of all time and the biggest success of Brubeck’s career. They wanted him to go home and write some dance tunes quickly. When he brought in his now-classic Time Out album, featuring “Take Five” and other pieces in odd time signatures, the record company told him it would never fly, since it’s impossible to dance to anything outside of a strict 4/4 meter. “There’s too much distance between the performer and the audience.” It’s that distance that he’s been trying to overcome over the years, convinced that the public, much more than the honchos of the record companies who often call the shots, can appreciate all the complexity and richness his music can hold. “You can’t hear anything at the Bowl,” he said. The Dave Brubeck Quartet, “Take Five” by Paul Desmond.īrubeck was in town to play that night at the Hollywood Bowl with his quintet.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)